On Semantic Agency

“The police officer keeps a watchful eye on the citizen.” Or perhaps “the citizen is subjected to surveillance.” On the importance of maintaining precision as to whom semantic agency belongs.

“The police officer keeps a watchful eye on the citizen.” Or perhaps “the citizen is subjected to police surveillance.” On the importance of maintaining precision as to whom semantic agency belongs.

In my work as a film subtitler, I use the translation strategy modulation very often, in all its forms and branched out subdivisions. One important factor in modulation is the fact that the process changes the semantic point of view of the source text. While that is often necessary, and usually perfectly justifiable, it does open the door to certain risks. Modulation will often manipulate the grammatical agency of a sentence, and could change the roles between the grammatical subject and grammatical object, or sometimes hide or camouflage the subject behind the veil of a passive construction. This is a lingustics problem sometimes described as who’s the doer and who’s the done-to.

The Russian sentence kalitka byla otkryta Olegom (the gate was opened by Oleg) implies that the mere fact that the gate was opened somehow ranks higher than the other fact that the deed was done by a man called Oleg. By using passive voice here, the grammatical agent is the gate, while the real, semantic agent, Oleg, is downplayed, and added at the end of the sentence.

The Russian sentence Oleg otkryl kalitku (Oleg opened the gate) puts the grammatical and semantic agent in the same place. Here, Oleg is the grammatical agent and the semantic agent, because he is logically the one who opened the gate.

Some languages use the former, passive, construction much more than other languages. Russian is by many claimed to have a proclivity for passive constructions. I will talk about possible reasons for that in a later blog post. Passive constructions are common in many languages, and in my work, I often find myself spending a long time deciding who’s the agent and who’s the patient in a sentence.

I recently translated one of those LA cop shows, where an abundance of camera angles document the daily life of American police officers in Los Angeles. Now, get this:

The passive construction the cocaine bag was tossed on the ground carries more ambiguity than the active construction the suspect tossed the cocaine bag on the ground. In the first example, we’re not sure who’s responsible for emptying the suspect’s pockets. The second sentence confirms that the suspect actively snuck out the cocaine bag from his own pocket, and tried to toss it away, which would probably be detrimental in the subsequent court process the suspect would have to go through.

Home Office

My office oversees the hilly east coast of Jutland. Sunrays occasionally enter. Coastal storms can really jolt the old building.

My office oversees the hilly east coast of Jutland. Sunrays occasionally enter. Coastal storms can really jolt the old building. Thankfully, a large firewood stove provides heat and comfort.

Translation Strategy

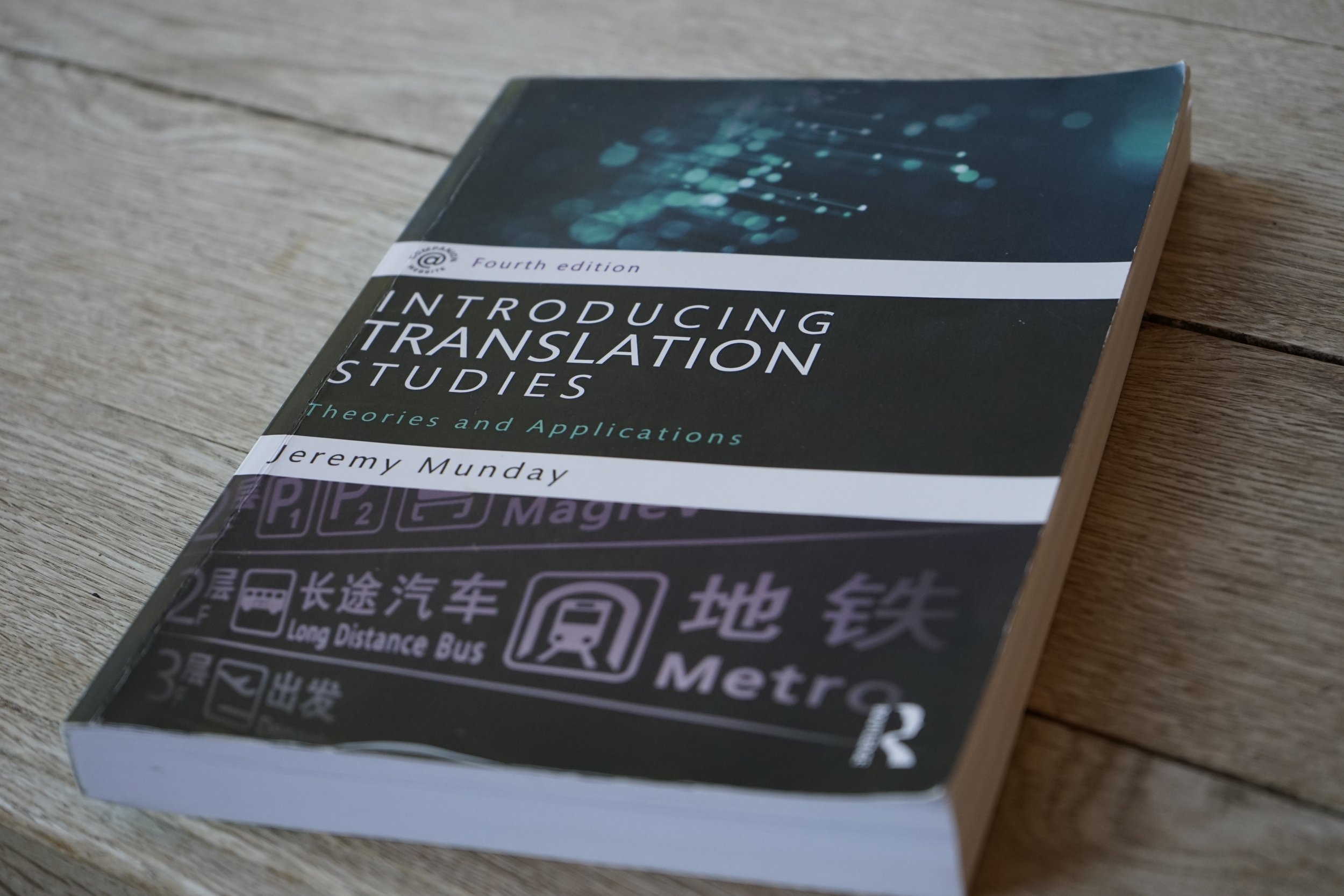

Following Munday’s book on translation studies, a guide to translation strategy.

Following Munday’s book on translation studies, a guide to translation strategy.

By Vinay and Darbelnet’s translation model (1995/2004), we operate with two main translation strategies. Direct translation and oblique translation (latin: indirect). Direct translation is described as a literal form of translation, while oblique translation allows the translator to take certain freedoms.

Vinay and Darbelnet’s model breaks down into seven procedures. The procedures are individual elements of translation strategy, of which the three first belong to the direct translation strategy, and the remaining to the oblique translation strategy.

(1) Borrowing

Source text words are transferred directly, or “borrowed”. For example, when sushi is translated sushi, and when computer is translated computer.

(2) Calque

Calque, meaning to copy or to trace, is another type of borrowing, sometimes also called a loan translation. A source text word, or an expression, is translated directly. An example would be the Adam’s apple being calque for the French pomme d’Adam.

(3) Literal translation

This procedure, also known as word-for-word translation, where sentence structure and words match in terms of style, content and intent. This procedure is easier to implement when source text and target text are of similar language families, or are closely related culturally, for example German and English. This procedure is harder, and sometimes impossible, to achieve if the languages and the cultures are very different, for example with Chinese into Dutch. The architects of this translation model, Vinay and Darbelnet, emphasize that when literal translation is not possible, oblique translation must be used.

(4) Transposition

Going into the remaining four oblique translation procedures, transposition covers the notion of “changing one part of speech for another”. For example, changing a noun for a verb, a verb for a noun, an adverb for a verb, et cetera. French dès son lever (upon her rising) may be translated, or transpositioned, into the English sentence as soon as she got up.

The adverb soon in the sentence He will soon be back may be transpositioned into a verb-centric sentence such as He will hurry to be back.

(5) Modulation

Modulation is a change in the semantic point of view. While many literal translations may be able to produce grammatically correct sentences, they will often be unusable anyway if they are unidiomatic or culturally improper in the target language. Modulation ensures that the target text is fitting for the target language and understandable for the intended audience.

An example being the time when, which translated into French could become le moment où (the moment where). Here, the key component of the sentence, when, has been changed into where, because of different preferred structures in English and French.

The sentence it is not difficult to show could become il est facile de démontrer (it is easy to show). The negating feature in the English sentence is lost due to other preferred structures in French.

Vinay and Darbelnet stresses that modulation is a key procedure in most translations, and they describe well executed modulation as the “touchstone of a good translator”.

A common problem when translation from Russian to English are active versus passive constructions. Russian language relies heavily on passive constructions, for example pis’mo napisano Ivanom (The letter was written by Ivan) instead of the more active construct Ivan napisal pis’mo (Ivan wrote the letter). This problem is not limited to Russian, as various languages rely on active and passive constructions to varying degree.

(6) Équivalence (or idiomatic translation)

Vinay and Darbelnet describe équivalence as a phenomena “where languages describe the same situation by different stylistic or structural means.”

The French comme un chien dans un jeu de quilles [like a dog in a game of skittles] could for example translates as like a bull in a china shop. The original image has not been recreated, rather a new one has emerged, but which recreates the same type of situation.

(7) Adaptation

An adaptation is changing a cultural reference because it does not exist in the target culture. Vinay and Darbelnet use the example of changing the reference of a game of cricket into une étape du Tour de France because a French audience may perceive a stronger connection to the cycling event.

Adaptations are in many cases very useful, and often strictly necessary. However, depending on context they can also damage an existing point or argument in the source text. The idea of a sleepy Wednesday morning county match at Lords [a London cricket ground] cannot be altered much reference-wise in other languages, let alone into a reference involving cycling.

(Following Jeremy Munday, 2016)

The Man in the Arena

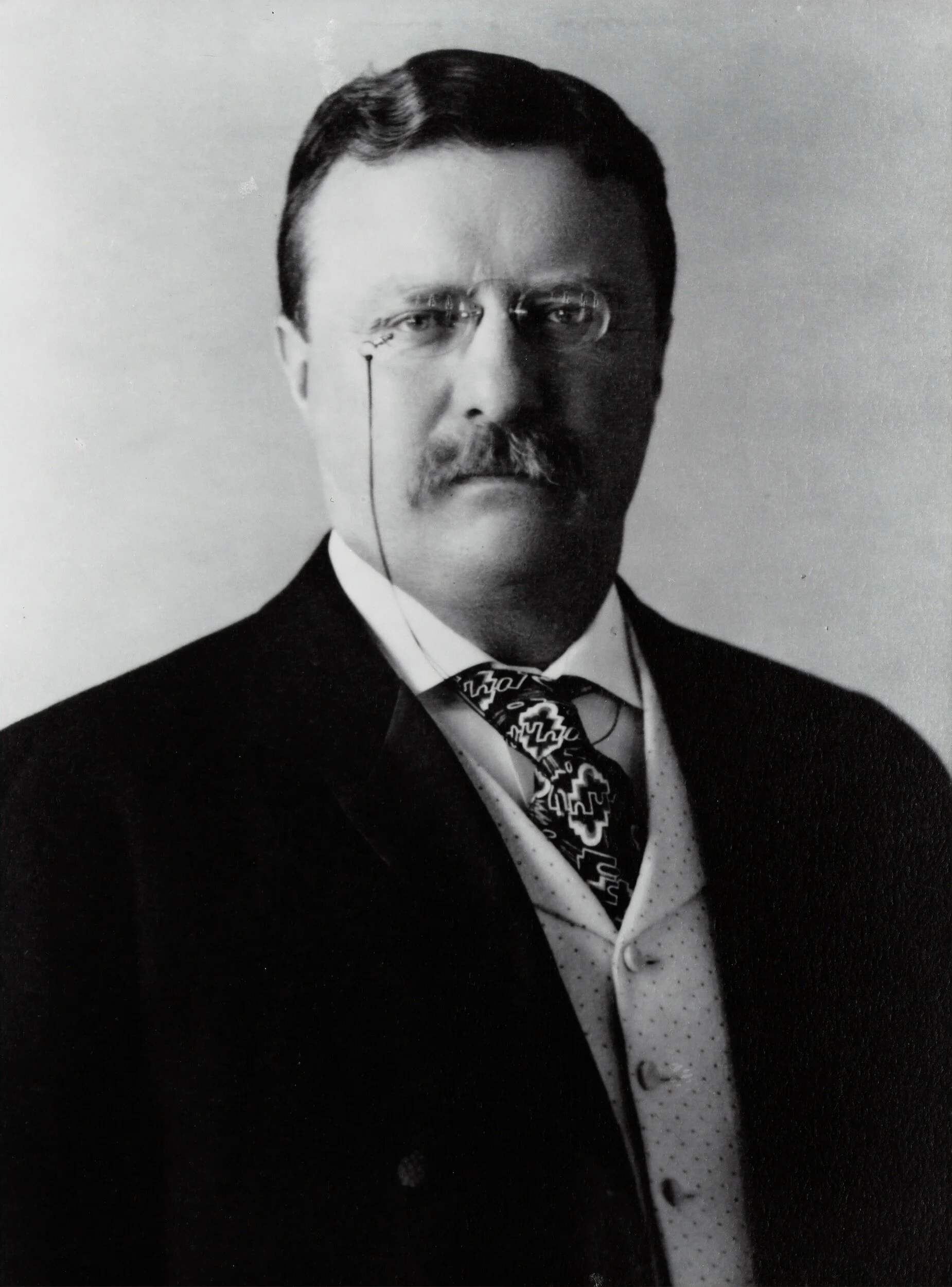

“It is not the critic who counts” - my experience translating Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 Sorbonne Address for a television media client.

Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 “Citizen in a Republic”-speech is especially known for a particularly poetic paragraph referred to as The Man in the Arena, which discusses the glory in having high personal ambitions, and striving for excellence despite facing great risks. Here’s an excerpt:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

(wikisource.org, U.S. Public Domain)

I recently had to translate this excerpt from Roosevelt’s speech into Danish for a customer to be subtitled on Danish television. It aired well, but I had three challenges with it.

Space constriction. This particular client allows up to 38 characters per subtitle line. While it is sometimes possible to use up two full lines of on-screen text, that is not always allowed due to timing constrictions in certain hectic parts of the show. As per client conditions, there are certain reading speed requirements for subtitles, severely limiting the amount of characters I may use. The character limit is a fact of life for me as a localization professional, but when translating poetry, it becomes an extremely limiting factor, pushing my creative, out-of-the-box thinking to the limits.

Time constriction. The localization industry is very clear in terms of what’s constitutes its intent: It’s creating a product which is readily understood by the local audience. This means my subtitles won’t stay on screen for long. Often just a single second. That’s why subtitles should be written in a way that they create an easily decipherable impact with the viewer - as fast as humanly possible. Dealing with poetry, the time constriction becomes a real head-scratcher.

Word-for-word or sense-for-sense? The age old question within translation studies is this: how literal should a translation be? A word-for-word approach to translation is very literal, and is very loyal to the style of the original text. But it makes for a clunky target text. Clunkiness is poison in the localization industry. Subtitles should be smooth and easily read on the screen. A sense-for-sense approach creates much more elegant and more understandable subtitles. There just one catch: Now, I’m creating a whole new work. Can I live up to that responsibility? When Roosevelt says timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat, it is now up to me to gather what that means in my locale (Danish), and adapt it so it fits the locale’s window for understanding. How do I recreate the impact Roosevelt’s speech had in his time and place? And does the target language and culture even possess the cultural framework needed to reproduce the source text message without sounding too foreign? The cultural gap between American and Danish cultural history is palpable, and bridging that gap requires me to make some difficult decisions as a translator.