The Man in the Arena

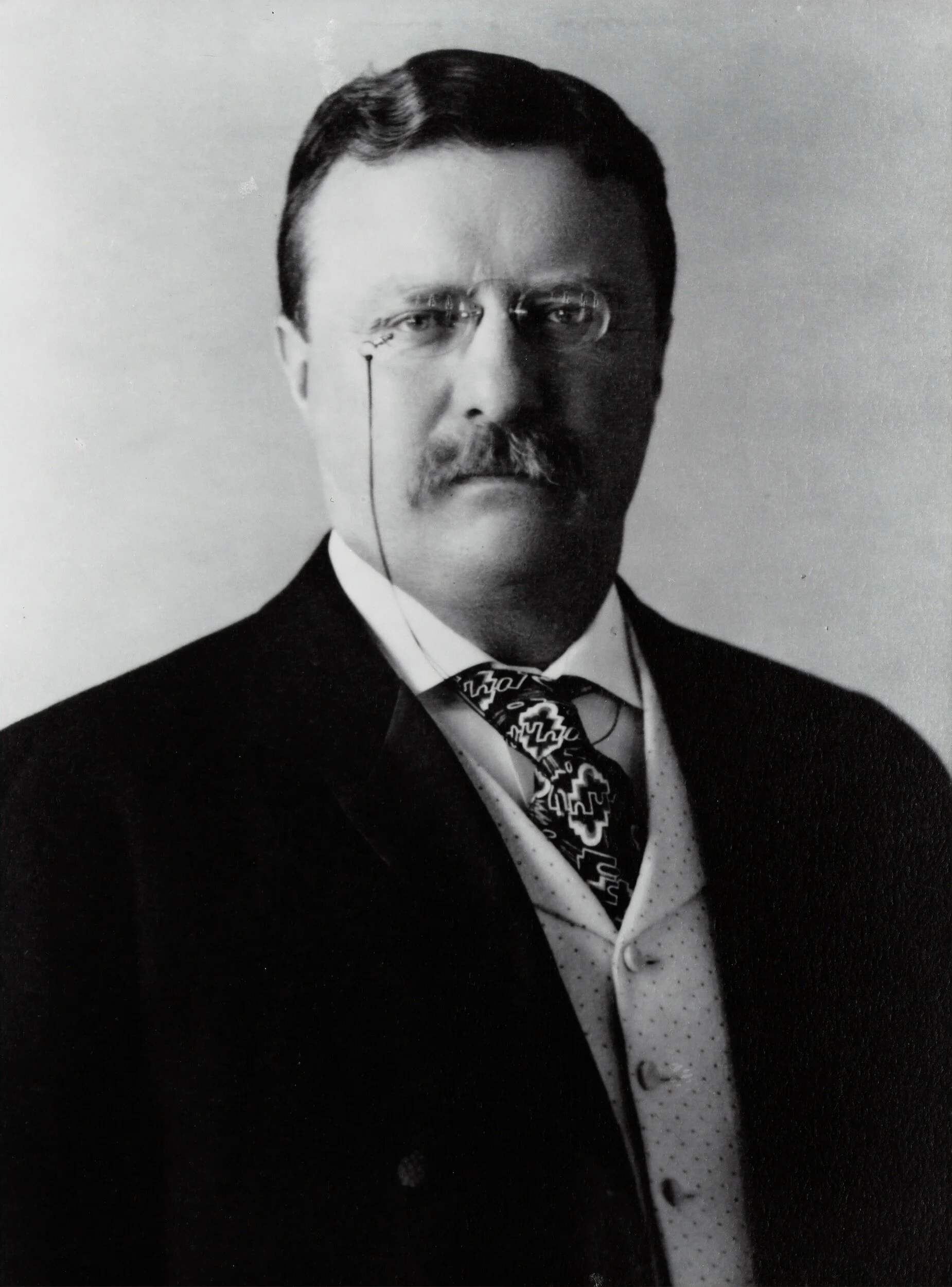

Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 “Citizen in a Republic”-speech is especially known for a particularly poetic paragraph referred to as The Man in the Arena, which discusses the glory in having high personal ambitions, and striving for excellence despite facing great risks. Here’s an excerpt:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

(wikisource.org, U.S. Public Domain)

I recently had to translate this excerpt from Roosevelt’s speech into Danish for a customer to be subtitled on Danish television. It aired well, but I had three challenges with it.

Space constriction. This particular client allows up to 38 characters per subtitle line. While it is sometimes possible to use up two full lines of on-screen text, that is not always allowed due to timing constrictions in certain hectic parts of the show. As per client conditions, there are certain reading speed requirements for subtitles, severely limiting the amount of characters I may use. The character limit is a fact of life for me as a localization professional, but when translating poetry, it becomes an extremely limiting factor, pushing my creative, out-of-the-box thinking to the limits.

Time constriction. The localization industry is very clear in terms of what’s constitutes its intent: It’s creating a product which is readily understood by the local audience. This means my subtitles won’t stay on screen for long. Often just a single second. That’s why subtitles should be written in a way that they create an easily decipherable impact with the viewer - as fast as humanly possible. Dealing with poetry, the time constriction becomes a real head-scratcher.

Word-for-word or sense-for-sense? The age old question within translation studies is this: how literal should a translation be? A word-for-word approach to translation is very literal, and is very loyal to the style of the original text. But it makes for a clunky target text. Clunkiness is poison in the localization industry. Subtitles should be smooth and easily read on the screen. A sense-for-sense approach creates much more elegant and more understandable subtitles. There just one catch: Now, I’m creating a whole new work. Can I live up to that responsibility? When Roosevelt says timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat, it is now up to me to gather what that means in my locale (Danish), and adapt it so it fits the locale’s window for understanding. How do I recreate the impact Roosevelt’s speech had in his time and place? And does the target language and culture even possess the cultural framework needed to reproduce the source text message without sounding too foreign? The cultural gap between American and Danish cultural history is palpable, and bridging that gap requires me to make some difficult decisions as a translator.